Saturday, November 16, 2024 05:46 PM

Graduate Unemployment Crisis in Pakistan

- High unemployment rate among educated graduates in Pakistan.

- Disconnect between education and job market needs.

- Need for universities to align curricula with industry demands.

Image Credits: dawn

Image Credits: dawnExplore the alarming graduate unemployment crisis in Pakistan and the disconnect between education and job market needs.

Education has long been heralded as the golden ticket to success, a pathway to employment, growth, and wealth. From a young age, children are taught that a good education is essential to becoming a ‘somebody’ in life. This belief drives parents to invest heavily in their children’s education, often spending thousands on entrance preparation for prestigious schools like Karachi Grammar School. These preparatory sessions not only focus on academic readiness but also coach parents on how to present their children in the best light to secure admission.

As students progress, universities such as the Institute of Business Administration, Lahore University of Management Sciences, and Agha Khan University become the ultimate goals for many. Families from upwardly mobile middle-income groups aspire to land six-figure salaries, believing that degrees from these institutions will open doors to lucrative job opportunities. Conversely, lower-middle-income families strive to provide their children with any form of education, hoping it will lead to a better life. Organizations like The Citizens Foundation share inspiring stories of how education can empower individuals and transform family destinies.

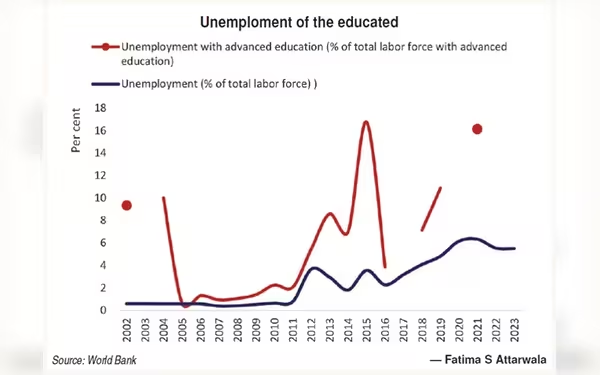

However, the reality of the job market raises serious questions about the effectiveness of this educational pursuit. Despite the widespread belief in education as a pathway to success, data reveals a troubling trend: the unemployment rate among graduates is alarmingly high. According to the World Bank, the unemployment rate for those with advanced degrees is higher than that of younger individuals in the country. The Higher Education Commission’s FY23 annual report indicates that there are approximately 470,000 graduates each year, including those with bachelor’s, master’s, and PhD degrees.

While the Labour Force Survey FY21 reported an increase of about 1.5 million jobs annually, these positions range from low-skilled roles to more specialized jobs. This raises a critical question: Are there enough jobs in the economy to absorb half a million graduates? Unfortunately, the data suggests that the likelihood of unemployment actually increases with higher levels of education in Pakistan. Macroeconomic conditions and reduced demand for labor contribute to the shrinking job market, but these factors alone do not account for the high rates of graduate unemployment.

Research conducted by the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics highlights that graduate unemployment is nearly three times the national average. In their paper titled “Disaggregating the Graduate Unemployment in Pakistan,” the authors point out that many students pursue degrees without a clear understanding of the job market. This disconnect is partly due to weak linkages between universities and industries. Pakistan ranks 63rd out of 163 countries on the World Bank’s University-Industry Linkage Index, indicating a significant gap in collaboration.

Moreover, the annual reports from the Higher Education Commission reveal that a large number of graduates are concentrated in arts and humanities. Ironically, while the number of universities in Pakistan has surged—over 100 new institutions have been established in the last decade—the quality and relevance of education often seem detached from the realities of the job market.

While education is undoubtedly important, the current landscape in Pakistan raises critical concerns about its effectiveness in securing employment. As the number of graduates continues to rise, it is essential for educational institutions to align their curricula with market needs and for students to be more informed about available job opportunities. Only then can the illusion of success through education be transformed into a tangible reality for future generations.