Sunday, December 22, 2024 01:54 AM

Polio Crisis in Pakistan: Urgent Action Needed to Protect Children

- Polio cases in Pakistan surge to 56 this year.

- Vaccine hesitancy fueled by misinformation and cultural beliefs.

- Government launches anti-polio campaign to reach vulnerable children.

Image Credits: geo

Image Credits: geoPakistan faces a polio crisis with rising cases and vaccine hesitancy. Urgent action is needed to protect children and eradicate the disease.

Pakistan is currently facing a significant challenge in its battle against polio, a disease that can cause paralysis and even death in children. The country has seen a troubling rise in polio cases this year, with 56 confirmed instances of the wild poliovirus (WPV) reported so far, compared to just six cases in the previous year. This alarming increase has raised concerns among health authorities and global organizations, who are calling for immediate action to protect the nation’s children.

One of the main factors contributing to this surge in polio cases is the forced repatriation of Afghan refugees. This situation has led to widespread displacement across Pakistan, disrupting established health services and making it difficult for children to receive their vaccinations. The wild poliovirus remains endemic in both Afghanistan and Pakistan, the only two countries where WPV transmission has not been halted. In 2024, Afghanistan has reported 23 cases of polio, and the Taliban government’s decision to suspend door-to-door vaccination campaigns has left many children vulnerable.

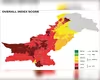

Most of the polio cases in Pakistan have been reported from Balochistan, particularly in areas close to the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. In Killa Abdullah, for instance, six cases have been confirmed, while other regions like Quetta and Zhob have also seen infections. The situation is not limited to Balochistan; Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Sindh have also reported multiple cases, highlighting the widespread nature of the crisis.

Misguided beliefs and cultural misconceptions have further complicated the fight against polio. Vaccine hesitancy is prevalent in many communities, fueled by misinformation that suggests the vaccine could cause infertility or is part of a foreign conspiracy. This distrust is particularly strong in regions where health outreach is most needed. For example, in Karachi’s Gadap area, an elderly resident named Shafiq expressed skepticism about the polio vaccine, claiming that diseases did not exist in his time and attributing their emergence to international vaccination efforts.

Despite these challenges, prominent Islamic scholars are stepping up to counter these misconceptions. Scholars like Imtiaz Ahmed emphasize that Islam encourages taking necessary measures to protect the health of families. He asserts that vaccinations are not only permissible but also a moral responsibility to safeguard children and the community.

To combat vaccine hesitancy, government officials must work closely with religious leaders to build trust within communities during immunization campaigns. This approach has proven effective in regions like Gilgit-Baltistan, where no polio cases have been reported since 2017. Increased awareness, high literacy rates, and community involvement have played a crucial role in this success.

Recently, the Pakistani government launched a third anti-polio vaccination campaign aimed at protecting vulnerable children. This campaign, which ran from October 28 to November 3, reached over 400,000 children under the age of five. However, resistance to vaccination remains a significant hurdle, particularly in areas like Ibrahim Hyderi in Karachi, where family dynamics often influence decisions about vaccinations.

The dream of a polio-free Pakistan hangs in the balance as the country grapples with rising cases and deep-rooted misconceptions. It is imperative for health authorities, communities, and partners to unite in this fight. By fostering trust, dispelling myths, and ensuring that every child receives their vaccinations, Pakistan can move closer to eradicating polio once and for all. The health of future generations depends on the actions taken today.